What Was the 1964 Freedom Summer Project?

Freedom Summer, 1964

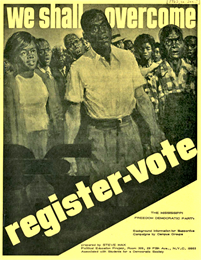

Images from visual materials in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Freedom Summer was a nonviolent effort by civil rights activists to integrate Mississippi's segregated political system during 1964.

Planning began late in 1963 when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to recruit several hundred northern college students, mostly white, to work in Mississippi during the summer. They helped African-American residents try to register to vote, establish a new political party, and learn about history and politics in newly-formed Freedom Schools.

Because black Mississippians were barred from Democratic Party primaries and caucuses, they challenged the right of the Party's all-white delegation to represent the state at the Democratic National Convention (DNC) in August.

Because black Mississippi residents were not allowed to vote, they held a parallel "Freedom Election" in November and challenged the right of the all-white Mississippi congressional delegation to represent the state in Washington in January 1965.

Residents and volunteers were met by extraordinary violence, including murders, bombings, kidnappings, and torture. Much of this was covered on national television and focused the country's attention on civil rights issues for the first time.

Public outrage helped spur the U.S. Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

"Freedom Summer" is a term invented after these events occurred. At the time, participants usually called it the Mississippi Summer Project.

Why Did Freedom Summer Happen?

Colored Entrance at Malco Theater, 1953

Memphis, Tennessee. In southern states, a closed society was enforced by laws created by white supremacists. The laws stipulated that African Americans would enter stores through separate entrances as a sign of being treated as a lower class of citizens. View the original source document: WHI 83204

For nearly a century, segregation had prevented most African-Americans in Mississippi from voting or holding public office. Segregated housing, schools, workplaces, and public accommodations denied black Mississippians access to political or economic power. Most lived in dire poverty, indebted to white banks or plantation owners and kept in check by police and white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. African-Americans who dared to challenge these conditions were often killed, tortured, raped, beaten, arrested, fired from their jobs, or evicted from their homes.

SNCC and CORE leaders believed that bringing well-connected white volunteers from northern colleges to Mississippi would expose these conditions. They hoped that media attention would make the federal government enforce civil rights laws that local officials ignored. They also planned to help black Mississippians organize a new political party that would be ready to compete against the mainstream Democratic Party after voting rights had been won.

Who Participated in Freedom Summer?

CORE Brochure on 'The Right to Vote,' 1962

Sumter, Mississippi. Photograph of a local resident by Bob Adelman. View the original source document: Congress of Racial Equality. Southern Regional Office Records, 1954-1966

More than 60,000 black Mississippi residents risked their lives to attend local meetings, choose candidates, and vote in a "Freedom Election" that ran parallel to the regular 1964 national elections. Several hundred African-American families also hosted northern volunteers in their homes.

Nearly 1,500 volunteers worked in project offices scattered across Mississippi. They were directed by 122 SNCC and CORE paid staff working alongside them or at headquarters in Jackson and Greenwood. Most volunteers were white students from northern colleges, but 254 were clergy sponsored by the National Council of Churches, 169 were attorneys recruited by the National Lawyers Guild and the Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee, and 50 were medical professionals from the Medical Committee for Human Rights.

Administratively, the project was run by the Council of Federate Organizations (COFO), an umbrella group formed in 1962 that included not just SNCC and CORE but also the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and others. SNCC provided roughly 80 percent of the staff and funding for the project and CORE contributed nearly all of the remaining 20 percent. The Mississippi Summer Project director was Bob Moses of SNCC and the assistant director was Dave Dennis of CORE.

Who Were the Key People Involved?

Lawrence Guyot Addressing a Group, 1964

Mississippi. View the original source document: WHI 97876

Fannie Lou Hamer on Television, 1964

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party candidate. View the original source document: WHI 97928

Freedom Means Vote For Victoria Gray, 1964

Mississippi. Along with Fannie Lou Hammer, Annie Devine, and Aaron Henry, she helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. View the original source document: WHI 97167

SNCC shunned the concept of powerful leaders. It made all its important decisions as a group, and conceived Freedom Summer as a grass-roots movement of people rising up to seize control of their own destinies. More than 500 individuals worked on the project full-time during the summer of 1964. A handful of those who played key roles were:

- Robert Moses

- He proposed the idea of Freedom Summer to SNCC and COFO leaders in the fall of 1963 and was chosen to direct it early in 1964. More than any other person, Moses could be said to have led Freedom Summer.

- Dave Dennis

- A veteran of earlier sit-ins and freedom rides, he was the leader of CORE's operations in Mississippi and Louisiana and assistant director of COFO. He led CORE's participation in Freedom Summer and, with Bob Moses, guided the project overall.

- Julian Bond and Mary King

- They ran the SNCC Communications Section, making sure that the national media was available to cover events and that project staff stayed informed and in-touch about the constant dangers.

- Lawrence Guyot (1939-2012)

- He was a driving force behind the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP).

- Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977)

- She was a leader of the MFDP who challenged the white-supremacist delegation to the DNC, ran for Congress in the Freedom Election in November, and helped lead the congressional challenge that followed it. Her impassioned plea for voting rights at the DNC was seen on national television by millions and epitomized Freedom Summer to many viewers.

- Annie Devine (1912-2000) and Victoria Gray (1926-2006)

- They were leaders of the MFDP who challenged the white-supremacist delegation to the DNC, ran for Congress in the Freedom Election in November, and helped lead the congressional challenge that followed it.

What Were the Goals for Freedom Summer?

Its overarching goal was to empower local residents to participate in local, state, and national elections. Its other main goal was to focus the nation's attention on conditions in Mississippi. Specific goals for the summer included:

- Increase Voter Registration

- Organizers wanted as many black Mississippians as possible to try to join the voter rolls. They correctly assumed that the majority woud be denied the right to vote and that this injustice could be widely exposed.

- Create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)

- Because officials prevented most blacks from registering to vote or participating in the regular Democratic Party, organizers tried to create a separate party and hold a parallel election. The MFDP was open to anyone (black or white), chose its platform and candidates democratically, and sent a delegation to the Democratic National Convention in August 1964 in hopes of being recognized as the legitimate voice of Democrats in Mississippi.

- Challenge the Democratic National Committee (DNC)

- At the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the MFDP contested the right of the white-supremacist delegation to represent Mississippi. They challenged it on the grounds that black residents had been systematically excluded from party meetings and primaries at which the delegates were chosen. Their testimony before the Democratic Party's Credentials Committee was broadcast throughout the nation.

- Set Up Freedom Schools

- Schools were established in local churches, storefronts, and other buildings so children and adults could learn black history, social studies, reading, and math, as well as develop leadership skills.

- Open Community Centers

- These were opened in existing buildings or new ones erected from scratch in order to provide child care, library books, meals, medical assistance, and other services denied to segregated black neighborhoods.

- Hold a Freedom Vote

- Since black residents couldn't vote in the regular election for president and local offices, organizers conducted a parallel election in which all residents could participate. It was scheduled just before the segregated regular election held on November 3, 1964.

- Challenge Exclusionary Congressional Elections

- After the all-white winners of the regular election were sent to Washington, D.C., the MFDP challenged their right to take seats in Congress because black residents had been systematically excluded from the electoral process.

Who Opposed Freedom Summer?

A number of groups opposed the project.

- Mississippi's Elected Officials

- Officials in Mississippi at all levels denounced the Summer Project. Its senators and governor publicly refused to obey federal integration laws, the state police nearly doubled in size, legislators passed new laws prohibiting picketing and leafleting, and local sheriffs and police chiefs expanded their forces and acquired new weapons.

- Business Leaders

- Businesses banded together in white Citizens Councils to coordinate punishment of African-Americans who participated in Freedom Summer. They foreclosed mortgages on black residents' homes, fired workers from jobs, banned customers from shopping in stores, and shut down food pantries for the poor.

- White Supremacy Groups

- Groups such as the Ku Klux Klan inflicted violence on black residents and civil rights workers. Between June 16 and September 30, 1964, there were at least 6 murders, 29 shootings, 50 bombings, more than 60 beatings, and over 400 arrests of project workers and local residents.

What Happened During Freedom Summer?

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: Background and Recent Developments, 1965

Mississippi. View the original source document: Lucile Montgomery Papers, 1963-1967

On the project's first day, June 21, three workers (James Chaney, Mickey Schwerner and Andrew Goodman) were kidnapped and murdered. The search for their killers dominated the national news and focused public attention on Mississippi until their bodies were discovered on August 4.

Only a few hundred new black voters were able to register, but the harassment and reprisals against them were widely covered in the national media. Public outrage helped swell support for new laws and federal intervention.

The MFDP convention drew hundreds of people and successfully launched the new party. Its delegates to the Democratic National Convention in August, however, were not recognized by party leaders and were not allowed to take seats.

More than 40 Freedom Schools opened in 20 communities. More than 2,000 students enrolled in classes led by 175 teachers.

During the unofficial Freedom Vote held October 31-November 2, more than 62,000 people cast ballots despite shootings, beatings, intimidation, and arrests. In most counties, Freedom Voters outnumbered regular Democratic Party voters.

The congressional challenge was launched on January 5, 1965. After nine months of legal maneuvering, the U.S. House of Representatives rejected the MFDP challenge and allowed the all-white Mississippi delegation to occupuy the state's seats.

What Did Freedom Summer Accomplish?

Americans all around the country were shocked by the killing of civil rights workers and the brutality they witnessed on their televisions. Freedom Summer raised the consciousness of millions of people to the plight of African-Americans and the need for change. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed Congress in part because lawmakers' constituents had been educated about these issues during Freedom Summer.

Mississippi's black residents gained organizing skills and political experience. In later years, when the federal government finally sent dozens of officials into local courthouses to enable African-Americans to vote and run for office, they were prepared to take part in the political process.

By the fall of 1964, many organizers and activists had become disillusioned. The brutality of the white power structure convinced some civil rights workers that nonviolence had failed. The refusal of the U.S. government to enforce its own civil rights laws disillusioned those who had hoped for federal intervention. The rejection of the MFDP challenges by the Democratic Party and the U.S. House of Representatives persuaded many activists around the nation that traditional politics would not secure basic civil rights. Some national leaders, such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, therefore began to urge African-Americans to seize their rights "by any means necessary." This sentiment helped create the Black Power Movement and organizations such as the Black Panthers.

What Happened After Freedom Summer?

The struggle against segregation and repression continued throughout the South. Conditions changed only after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 legally empowered the federal government to send its own officials into local courthouses. By the end of 1966, more than half of African-Americans in southern states had registered to vote. In the years that followed, many were elected to local offices such as mayors, school boards, and chiefs of police.

Many SNCC and CORE staff went on to important careers in public service. John Lewis of SNCC was elected to the U.S. Congress, Mary King of SNCC oversaw the Peace Corps and Vista under President Carter, and her colleague Julian Bond headed the NAACP after serving many years in the Georgia legislature. Other staff became influential professors, attorneys, and civil servants.

Many of the northern volunteers went on to start or to lead important anti-war, women's, and gay rights organizations. For example, voter registration worker Mario Savio started the Berkeley Free Speech Movement; freedom school teacher Chude Pam Parker Allen helped organize women's liberation groups in New York and San Francisco; and Barney Frank, a volunteer in the Jackson office, became one of the nation's first openly gay politicians in the U.S. Congress. Many others devoted their careers to legal or social services for the disadvantaged.

Learn More

View the Freedom Summer Digital Collection

Over 40,000 pages of original documents are are available online.See More About Freedom Summer

Overview of Freedom Summer resources with links to specific content.

Learn More from Other Institutions

Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive

Visit over 7,000 pages of digitized photographs, letters, diaries, and oral history transcripts, as well as finding aids for manuscript collections that are not online. Created by the University of Southern Mississippi.The King Center

See an archive of nearly one million pages that The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change has maintained for over a quarter century. It has recently begun putting selections of the most important materials online.Civil Rights Movement Veterans

View documents, letters, reports, stories, memoirs, and other materials contributed by Civil Rights workers on this very large and rich website.SNCC Legacy Project

See essays, calendars of upcoming events, and more from this website run by former staff and volunteers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Have Questions?

Email us to get answers to your questions about Freedom Summer.