Milwaukee, Wisconsin History

History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin

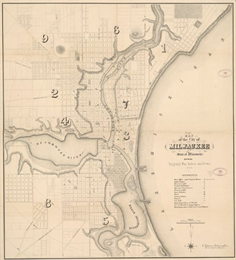

Map of Milwaukee, 1862

Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Drawn the second year of the Civil War, this 1862 map of Milwaukee shows post offices, light houses, beacon lights, county buildings, elevator warehouses, flouring mills, iron foundries, hotels, school houses, churches, boundary lines of wards, city hall, the Menominee River and the Milwaukee River. View the original source document: WHI 6921

Wisconsin's largest city lies on Lake Michigan, where the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic Rivers come together. People had lived there for more than 13,000 years before the first Europeans arrived. At that time Milwaukee was neutral ground shared by several American Indian tribes.

Fr. Jacques Marquette left the first written record of it in 1674, and other French explorers referred to it in 1679, 1681 and 1698. The earliest mention of Europeans is a reference by Lt. James Gorrell to an unnamed fur trader at Milwaukee in 1762; at least four others traded there before 1800. In 1763, Milwaukee bands of Potawatomi, Ottawa, Ojibwe and Menominee joined Pontiac's Rebellion against the British, and 15 years later they supported the colonies during the American Revolution.

The city's modern history began in 1795 when fur trader Jacques Vieau (1757-1852) built a post along a bluff on the east side, overlooking the Milwaukee and Menomonee rivers. Vieau was a seasonal resident, and in 1818 transferred his Milwaukee assets to his son-in-law, Solomon Juneau (1793-1856). Juneau is generally considered not only the city's first permanent white resident but also its founder.

In 1822 Solomon Juneau built the first log cabin in Milwaukee and two years later, the first frame building. In 1831 he became an American citizen and began to learn English, and in 1833 he partnered with Morgan Martin (1805-1887) to develop a village on the east side. In 1835 Juneau and Martin laid out streets, platted lots, and began selling them to new settlers. Over the next two decades Juneau served as Milwaukee's postmaster and mayor, built its first hotel and courthouse, started its first newspaper, and backed almost every public improvement.

Between 1835 and 1850, Milwaukee's population grew from a handful of fur traders to more than 20,000 settlers. Three separate villages were started: Juneau's, east of the Milwaukee River and north of the Menomonee; Byron Kilbourn's across from Juneau's, on the west bank of the Milwaukee; and Walker's Point, across the Menomonee from the other two. In 1846 they incorporated into a single city. By then Milwaukee rivaled Chicago in size, wealth and potential, but in 1848 the Illinois city secured railroad and telegraph connections that enabled it to eclipse Milwaukee.

Between 1846 and 1854, a wave of German immigrants arrived, bringing with them expert industrial skills, refined culture, liberal politics, and Catholicism. Milwaukee soon became a center of foundry, machinery, and metal-working industries, as well as a center for brewing and grain trading. During the last third of the 19th century, visitors often commented on Milwaukee's refined German culture, European elegance, and prosperity (while usually overlooking the laborers who produced its wealth with the toil of their hands). On Oct. 28, 1892, a fire in the Irish third ward wiped out sixteen square blocks, leaving 2,000 immigrant working-class residents homeless.

During the first half of the 20th century, Milwaukee became known for its "sewer socialism." City leaders sought to clean up neighborhoods and factories with new sanitation systems, municipally-owned water and power systems, community parks, and improved educational opportunities. Victor Berger (1860-1929) became the symbol of Milwaukee socialism by organizing voters into a highly successful political organization based on Milwaukee's large German population and active labor movement.

During the 1930s the city was hit especially hard by the national depression: the number of people with jobs fell by 75% and 20% of residents needed direct relief from the government. The number of strikes increased sevenfold between 1933 and 1934, and conditions only improved when World War Two demanded huge amounts of factory goods between 1941 and 1945.

During the war, many African-Americans from Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee and elsewhere in the South came to work in Milwaukee's factories, and most stayed to raise their families after the war. By the 1960s Milwaukee was 15 percent African-American, but most black residents were clustered in a near-north neighborhood that suffered from unemployment, poverty, and segregation.

Local statutes, real estate agents, and lending institutions conspired to keep African-American citizens confined to the inner city, and segregated neighborhoods produced segregated schools. Two decades of struggle by black leaders such as Vel Phillips (b.1924) and Lloyd Barbee (1925-2003), supported by white allies like Fr. James Groppi (1930-1985), were needed to force city officials to obey federal desegregation laws. When local codes and practices began to change in 1968, white residents moved out, leaving Milwaukee one of the most segregated cities in America today.

Since 1970, manufacturing has ceased to dominate Milwaukee's economy, although traditional industries such as heavy machinery, tools, engines and brewing survive. Instead, businesses in the service sector, such as health care, banking, insurance, and retail sales, now employ most Milwaukee workers. Such businesses have spread north, west, and south out of the city along interstate highways, until the community of greater Milwaukee stretches nearly to Racine, Washington, and Jefferson counties.

See More About Milwaukee

See more images, essays, newspapers, museum objects and records about Milwaukee.

[Source: Wisconsin Historical Society Collections]