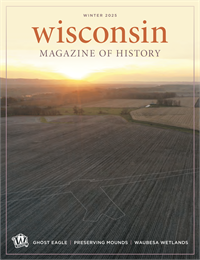

Current Issue of the Wisconsin Magazine of History

Winter 2025, Volume 109, Number 2

Ghost Eagle Mound in Muscoda, Wisconsin, November 2023. Five weeks after the fall equinox, Ghost Eagle is in near alignment with the setting sun as it passes behind the mound groupings at Frank’s Hill.

Featured Story

Earth Guardians: A Ho-Chunk Family’s Efforts to Preserve Indian Mounds

By Ritchie Brown and Casey Brown

Ritchie and Casey Brown have more in common than their love of fishing. Every couple of weeks over the past two years, this father and son have met at various locations across southern Wisconsin—Muscoda, Madison, and Lake Mills, among others—to film Ritchie’s work preserving the mounds built by their Ho-Chunk ancestors. Casey is a comedian and an Emmy Award–winning documentary filmmaker, and Ritchie, retired head of the Ho-Chunk Department of Natural Resources and a Distinguished Elder, has been studying mounds since the 1980s when Casey was a young kid. In this candid back-and-forth memoir, they revisit the turning points that led them to a shared love of their cultural heritage, from Ritchie pulling Casey out of bed for mound cleanup as a teenager to the pandemic years, when they both worked for the Ho-Chunk Nation. Casey writes, “I learned to persist from my father. He learned to persist from the mounds. . . . My jaaji (dad) dedicated his life to rediscovering the story of the mounds. I am only starting to rediscover his.”

Charles Brown poses near a historic tablet marking one of a row of conical burial mounds on the north shore of Lake Wingra in Madison in 1939.

Unvanishing: Indigenous Wisconsin and the Legacy of Charles Brown

By Stephen Kantrowitz

Wisconsin archaeologist Charles “Charlie” Brown (1872-1946) dedicated much of his professional life to recording and preserving Wisconsin’s Indian mounds. While he is justly celebrated as the father of Wisconsin archaeology and of our state’s historic preservation efforts, he also worked in ways that now seem completely discordant with a spirit of collaboration. While Brown played a crucial role in preserving the state’s burial mounds, shepherding the first of the state laws protecting Native American graves and cultural sites in 1911, he also excavated some of them and super¬vised or encouraged others as they did so, paying little heed to those whose ancestors may have been buried within them. As author Stephen Kantrowitz discovers, Brown’s belief that Native nations and peoples were remnants of the past blinded him to their continued vitality and agency in the present, even as he built professional connections within the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, and Potawatomi Nations. His work, while invalu¬able in many ways, is not the whole story.

Cal enjoying the wetlands in the town he loves. The photo comes from a documentary filmed and produced in 2024 by Cal’s grandson, Ben Albert, who is part of the current generation working to preserve the Waubesa Wetlands.

Stewards of Land and Life: Nurturing Earth Stewardship in a Wisconsin Town

By Calvin B. DeWitt

In 1972, after relocating to Madison to take a professorship at the UW, field biologist Cal DeWitt bought a house on the Waubesa Wetlands just south of the city, with dreams of raising his young family in an environment teeming with life and studying its unique ecosystem. Soon, he discovered he was also part of a thriving human community in the small Town of Dunn. In this heartfelt memoir, DeWitt recounts his years as a town supervisor, connecting with the people of Dunn and learning from them while also fostering earth stewardship as a central value in town planning. Fifty years later, those efforts are still shaping the Town of Dunn.

Book Excerpt

Bamboo Son: A Hmong Refugee’s Search for Identity and the American Dream

By Pao Lor

In this follow-up to his acclaimed memoir, Modern Jungles, Pao Lor picks up his story as a young Hmong immigrant building a life in a new home while navigating his journey into adulthood. Bamboo Son releases in March 2026 from the Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

A subscription to the Wisconsin Magazine of History is a benefit of membership to the Wisconsin Historical Society. The current issue, described above, will become available in the online archives as soon the next issue is published.

Become a Wisconsin Historical Society member today!

Subscribe today by becoming a member

Learn More:

View the Wisconsin Magazine of History Archives