Diseases and Epidemics in Wisconsin

Beating the Bug, 1968

Fire fighter gets a flu shot made available to city workers in the lobby of the municipal building to avoid contracting the Hong Kong flu. View the original source document: WHI 8562

Throughout history the movement of people has played a major role in the transmission of disease. Migration, trade, and war have allowed diseases to travel from one environment to another, often with far-reaching social consequences. The devastation of Native American populations, for example, was one such consequence of European settlement in the Americas. Introduced diseases probably reached Wisconsin before European explorers themselves. In the 50 years following Hernando de Soto's invasion of the lower Mississippi in 1539, disease killed 90 percent of the Indians living in the middle Mississippi Valley — Indians with whom Wisconsin's Oneota culture had traded for centuries. Many archaeologists have speculated that epidemics of measles or smallpox may have swept through Indian communities in Wisconsin long before Jean Nicolet stepped ashore in 1634.

When the French arrived and began living in Indian villages in the 17th and 18th centuries, diseases once again broke out. "Maladies wrought among them more devastation than even war did," wrote contemporary French visitor Bacqueville de la Potherie, "and exhalations from the rotting corpses caused great mortality."

Smallpox continued to rage through many Indian communities in the 1830s. Introduced by white explorers in 1760, smallpox epidemics repeatedly decimated Indian tribes. Surgeon and naturalist Dr. Douglass Houghton administered more than 2,000 vaccinations to Indians in the Chippewa region over the course of his two months exploring with Henry Schoolcraft in 1832, undoubtedly saving many Indian lives. Houghton estimated that the disease had appeared among the Chippewa at least five times in the previous 60 years.

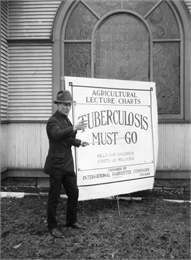

Man Delivers Lecture on Tuberculosis in front of Church, 1924

Man appearing to deliver a lecture on tuberculosis prepared by International Harvester's Agricultural Extension Department. View the original source document: WHI 8577

The Malaria and Cholera Epidemics

Epidemic disease was not confined to Indians, however. Malaria (known at the time as intermittent and remittent fever) was common among French, British, and later American troops. It reached epidemic proportions in the summer months. Military posts on the Wisconsin frontier in the 1820s and 1830s usually had a hospital and surgeons' quarters, though the service was often poor and inadequate. At Fort Crawford, 154 of the 199 men stationed there in the summer of 1830 had malaria. Even so, despite its high occurrence, few men actually died. Cholera, on the other hand, was a far more dreaded disease that spread with frightening speed and exacted a far higher death toll on Wisconsin residents.

Immigrants and Disease

When thousands of immigrants poured into Wisconsin in the 1840s, disease caught them unprepared. All of the diseases that plagued Europe were in Wisconsin as well: measles, mumps, and whooping cough to name a few. In newly settled areas the incidence of typhoid fever and other communicable diseases rose rapidly.

Though people were aware of the sickliness in new settlements, few knew the real cause. Many people assumed it was a symptom of the settlement process itself, a miasma rising from the decomposition of logs, freshly turned soil, and swamps and bogs. Most expected these conditions to pass as settlements became more established. Vaccinations, although known, were often unavailable, and smallpox sometimes infected entire villages. Cholera epidemics also swept Wisconsin, as they did much of the nation, from 1832 to 1834 and again from 1849 to 1854, the worst of which was centered in Milwaukee.

Other epidemics arrived aboard ships and stagecoaches. In 1850, 300 Norwegians and Swedes, most of whom were infected with typhoid fever, arrived in Milwaukee aboard the ship Alleghany. In the absence of sewage systems, clean water, systematic street cleaning, and effective methods for keeping and preserving foods, waterborne and airborne diseases were constant threats.

City Hospital, 1892

View across street of City Hospital in Janesville. Early hospitals were much smaller than their modern counterpart, and most patients sought treatment at home. View the original source document: WHI 34630

Medical Care and Treatment

To stem the tide of disease, Milwaukee passed ordinances that fined ship captains and stage drivers who brought sick passengers. A board of health was also established to investigate the causes of diseases and to provide a pesthouse for the infected. In 1847, all Milwaukee residents were required to receive smallpox vaccinations.In 1848, the Sisters of Charity opened Wisconsin's first hospital.

Throughout the 19th century, hospitals were inaccessible to the vast majority of Wisconsin residents. Doctors usually came to patients rather than the other way around. The most prevalent diseases were pneumonia, bronchitis, tonsillitis, mastoiditis (infection in the bone behind the ear), pleurisy (inflammation of the lungs),, and tuberculosis. Smallpox, cholera and typhoid fever remained problematic as well.

Deadly Spanish Flu

The most serious and deadly disease epidemic of the 20th century came to Wisconsin in September of 1918. The Spanish flu, or "la gripe," claimed the lives of more than 8,400 Wisconsin residents between the outbreak of the pandemic and May 1919. Declared by the State Board of Health the most "disastrous calamity that has ever been visited upon the people of Wisconsin," the Spanish flu swept across America in under seven days. More than 100,000 people were infected in Wisconsin alone. The devastation wrought by the flu in just a few short months claimed an estimated 50 million lives worldwide. It remains to this day the most destructive disease pandemic in world history.

Discovery of New Drugs and Treatments

The advent of penicillin and antibiotics in the years after the Great Depression led many in the medical profession to believe that infectious diseases would soon cease to pose a major threat. While the polio epidemic of the 1950s was fearsome, the promise that new medical technology could cure diseases seemed to be confirmed by the development of a vaccine. Seasonal flu outbreaks again reached pandemic levels in 1956-1958 with the Asian flu and again in 1968-1969 with the Hong Kong flu, though no where on the level of the 1918 Spanish flu.

Disease remains a part of life in Wisconsin, though the constant threat of contagion has lessened over the decades with new medical innovations, treatments, and vaccines.