Social Security: The Wisconsin Connection

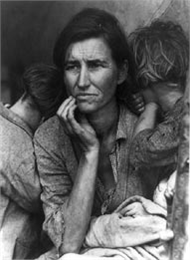

Migrant Mother, 1936

This classic photo of a Depression-era family captured the anguish of the times. Source: Photo by Dorothea Lange for the Resettlement Administration./p>

Recent interest in reforming Social Security has led an increasing number of people to ask us for background on the program, especially its Wisconsin connections. We've created this page to explain how the original Social Security program came into being in 1935, and the prominent part Wisconsin had in designing and administering it. Beneath each of the summary paragraphs below are links to original documents, memoirs, speeches and interviews that have been digitized by the Society, the Social Security Administration or the Library of Congress. For more information, especially about the evolution of the program after the 1930s, consult the "Brief History" on the comprehensive website prepared by the Social Security Administration.

- Why was a Social Security program needed?

- How was the original 1935 program created?

- What's the Wisconsin connection?

- What did the program accomplish in its first years?

1. Why was a Social Security program needed?

Between 1890 and 1930 major shifts occurred in the ways Americans supported themselves. Increasing numbers of people began to live and work in cities and suburbs rather than in small towns and on farms. Many young people left rural areas, where multi-generational families had always produced much of their own food, shelter and clothing, and relocated in urban areas. In cities new manufacturing techniques such as assembly lines reduced the number of jobs needed to provide basic commodities. Instead of creating objects, by 1930 many jobs provided services such as retail sales or cooking in restaurants. It was not possible to grow one's own food or make one's own clothing. Instead, large numbers of people made money with which to buy those things.

During the 1920s these changes created great wealth as business expanded, and to fuel that growth many companies borrowed money from banks to expand production. At the same time, private investors borrowed large sums from banks to buy shares of stock and get a piece of the action. As the Roaring '20s progressed, demand for stocks and their prices both continued to rise.

But on October 29, 1929, many more people tried to sell stock than tried to buy new shares. Stock prices therefore dropped far below what people had paid for them, and within hours investors who had owned great wealth on paper found themselves unable to pay back their bank loans. Over the next 90 days, the stock market lost 40 percent of its value and $26 billion of wealth disappeared. Businesses could not raise capital to produce goods and services or pay workers, and employees began to be laid off. Consumers bought less because they had lost money in the stock market or even their jobs. Banks began to find themselves in the same position as individual investors, owing more money than they possessed. When word of this leaked out, individual depositors rush to get their cash out of their local banks. During 1932 and 1933 banks failed by the thousands. By the mid-1930s, the combination of these forces had led to millions of unemployed workers, old people with little or no help from their families, parents unable to support their children, and businesses paralyzed. The human suffering caused by the failure of the economic system was on a scale never before seen in a depression.

When the Roosevelt administration took office in 1933, its major challenges were to alleviate that suffering and to restart the gridlocked economy. In a June 8, 1934, message to Congress, Roosevelt expressed the need for a social security program this way: "Among our objectives I place the security of the men, women and children of the nation first. This security for the individual and for the family concerns itself primarily with three factors. People want decent homes to live in; they want to locate them where they can engage in productive work; and they want some safeguard against misfortunes which cannot be wholly eliminated in this man-made world of ours."

- View pictures of Wisconsin residents and officials trying to cope with Depression conditions.

- Pictures from the Great Depression by the federal Farm Security Administration.

- The government explains why Social Security was needed in a 1937 pamphlet.

Edwin E. Witte, 1928 ca.

Portrait of Edwin Witte, chief of the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Service from 1922-1933. While the executive director of the President's Committee on Economic Security under U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, he helped develop during 1934 the policies and the legislation that became the Social Security Act of 1935. Because of this he is sometimes called "the father of Social Security." View the original source document: WHI 54544

2. How was the original 1935 program created?

At the end of June 1934, the Roosevelt administration convened a committee to research the problems faced by millions of Americans, and recommend a solution. Called the "Committee on Economic Security," it was chaired by University of Wisconsin economist Edwin E. Whitte, and assisted by a 23-member "Advisory Council to the Committee on Economic Security." Witte's group met from August 1934 until January 1935, when it submitted its report to the president, who forwarded it to Congress.

The committee looked at a wide variety of measures proposed or adopted in many U.S. states and foreign countries. Its workings are recalled in the speeches and interviews linked below. On January 17, 1935, the committee recommended federal old-age insurance, joint federal-state public assistance and unemployment insurance programs, extension of services to people with disabilities, children and child welfare agencies, and job training services. Hearings quickly began before the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee to turn the recommendations of Witte's committee into law. The original Social Security bill passed the House by a large margin on April 19, 1935, and was approved by the Senate Finance Committee two months later. It was signed by President Roosevelt on August 14, 1935. The bill provided for unemployment compensation; old-age benefits; aid to homeless, neglected, dependent and crippled children; and federal aid to state and local public health agencies.

The federal government then faced the challenge of getting employers and workers to sign up. Social Security retirement accounts needed to be created, cards had to be issued to workers and other beneficiaries, and accounting procedures had to be established. All this required administrative work and a public education campaign that lasted throughout the 1930s.

- Former Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins recalls why and how the bill was drafted.

- A 1936 U.S. government pamphlet explains how the new program works.

- A 1941 folding brochure uses cartoons to educate workers and employers.

John R. Commons, 1920 ca.

John R. Commons, a University of Wisconsin professor, is shown standing outside Sterling Hall with his hat on the ground at his feet. View the original source document: WHI 5115

3. What's the Wisconsin connection?

The conceptual underpinnings of Social Security came directly from the "Wisconsin Idea," the concept that government and academic experts should help solve social and economic problems, which dated from Wisconsin's Progressive-Era administrations. The designers of the Wisconsin Idea and the programs that expressed it, including economists John R. Commons and Richard T. Ely and Legislative Reference Bureau chief Charles McCarthy, were the mentors of Witte and the other principal authors of the Social Security Act.

The two acknowledged designers of the original Social Security Act were Arthur Altmeyer and Edwin Witte. Both were Wisconsin natives, Altmeyer from DePere and Witte from rural Jefferson County. In the 1920s Altmeyer was Secretary of the State Industrial Commission (predecessor of the current Department of Workforce Development), and Witte headed the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, which drafts bills at the request of lawmakers. Both were also on the University of Wisconsin-Madison faculty. When President Roosevelt was elected in 1932, he chose Altmeyer to be assistant secretary of labor, and Altmeyer drafted the presidential executive order which established the Committee on Economic Security. He helped select Witte to chair that committee and was himself a key committee member. When Witte came to Washington to head the CES in 1934, he brought his prize student, Wilbur Cohen of Milwaukee, along as a research assistant.

After passage of the act, Witte returned to UW-Madison while Altmeyer and Cohen stayed in Washington to administer the program for more than 30 years. Altmeyer was the administrative head of Social Security from shortly after the act's passage until 1953, first as chair of the Social Security Board and, after an administrative reorganization, as Commissioner of Social Security. Cohen became the director of the Social Security Administration's Division of Research and Statistics. In the 1960s Cohen became the lead administrator for the Social Security program. John F. Kennedy appointed him assistant secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and he served as undersecretary and then secretary of HEW under President Lyndon Johnson, in both roles effectively running Social Security.

- Read the opening testimony of Edwin Witte before Congress in January 1935.

- Read a 1955 conversation between Witte and Cohen looks back at the program's origins.

- Cohen recalls "Arthur J. Altmeyer: Mr. Social Security" in a 1973 speech.

Banquet Celebrating the Third Anniversary of the signing of the Social Security Act, 1938

rom left to right: David J. Lewis, Congressman from Maryland, and Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York, co-sponsors of the Social Security Act; Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins and Arthur J. Altmeyer. View the original source document: WHI 104670

4. What did the program accomplish in its first years?

In August 1938, three years after the bill was signed, the Social Security Board summed up its achievements to that point. The pamphlet linked below concisely evaluates the act's five main programs. It defines the hazard or risk that each was meant to correct, shows what happened to people prior to 1935, and describes how the Social Security program addressed problems. The phamplet concludes: "At the third-year milepost, the road back shows well over 30,000,000 men and women now building up insurance against want in their old age; 25,500,000 workers who have earned some credit toward insurance during temporary unemployment; about 2,350,000 of the needy receiving assistance in their own homes; and health and welfare services reaching out into all parts of the country."

More specifically, the pamphlet shows that in Social Security's first three years: more than 39 million workers had signed up for social security retirement accounts; more than 25.5 million workers had been covered by unemployment compensation; nearly 1.7 million old people were already receiving monthly cash allowances; $47.6 million had been paid by the federal government to support dependent children; and more than 39,000 needy blind persons were receiving monthly cash allowances.