Surveyor's Tree Blaze

Wisconsin Historical Museum Object – Feature Story

Treaty tamarack, 1840

Treaty tamarack in Florence, Wisconsin, marking the beginning of the boundary line between Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan as marked by Cram in 1840. This photograph of the tree was taken about a century later. View the original source document: WHI 31060

Michigan-Wisconsin border, 1838

This 1838 map erroneously shows a continuous water border (highlighted here in red) between Michigan and Wisconsin. Source: T.J. Cram’s report on his 1840 expedition to map the Michigan-Wisconsin border in Wisconsin Historical Society Archives Collection

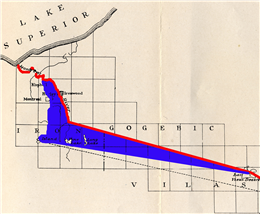

Gogbic region, 1908

Map detailing the area of the Gogebic region (shaded here in blue) claimed by Michigan in its 1908 state constitution. The red line indicates the original, and current, state border. Source: Brief of Defendant, State of Wisconsin in the 1923-26 Supreme Court case in Wisconsin Historical Library Collection

Gogebic Miners, 1886

Gogebic Range miners, Hurley, Wisconsin 1886. View the original source document: WHI 23380

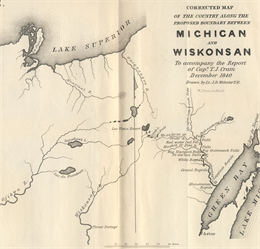

Map from report by T.J. Cram

Map from report by T.J. Cram after his 1840 expedition, showing the overland gap between the Montreal and Menominee Rivers, as well as the headwaters of the Wisconsin and Ojibwa (Chippewa) Rivers. Source: T.J. Cram's report on his 1840 expedition to map the Michigan-Wisconsin border in Wisconsin Historical Archives Collection

Surveyor's tree blaze from the 1841 expedition to lay out the boundary between Wisconsin and Michigan, found at Trout Lake,

Vilas County, Wisconsin.

(Museum object #1977.97)

Surveying is the means by which European settlers turned the North American landscape into property. They created new legal realities by dividing the country into discrete parcels with imaginary lines, but attaching these imaginary lines to the physical landscape often proved troublesome. In the nineteenth century, surveyors typically used natural features (rivers, lakes, peaks) when they could, and pounded stakes or carved available trees, like the one featured here, where nothing more permanent was available. Despite these efforts, ambiguity persisted.

This surveyor's mark or "blaze" was made on a tree growing on the shore of Trout Lake in Vilas County, about 10 miles north of Minocqua, Wisconsin. It bears

the names T.J. Cram and D. Houghton, and the date August 11, 1841. Captain Thomas Jefferson Cram (1804-1883) was an Army engineer, and Douglass Houghton (1809-1845) was a doctor, scientist, and Michigan's first State Geologist. In the summer of 1841, the two men led a survey party to establish the Upper Peninsula border between the State of Michigan and the Wisconsin Territory. They left this blaze as evidence of their work.

In June 1838, shortly after Michigan had become a state, Congress adopted an act that legally described the Wisconsin-Michigan boundary. This description was based on a map which indicated that both the Montreal River, which flows northwest into Lake Superior, and the Menominee River, which flows southeast into Green Bay, arose from Lac Vieux Desert, a lake on the border of present day Forest County. Both the erroneous map and the resulting legal border description presumed a nearly continuous waterway separating the two states. Efforts to physically survey this border languished for several years until responsibility was transferred to the War Department's Bureau of Topographical Engineers, which assigned the job to Capt. Cram. As superintending topographical engineer for Wisconsin, Cram's responsibilities had included constructing military roads and producing maps of the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers.

In the summer of 1840, Cram led his party up the Menominee River to its source at Brule Lake (not Lac Vieux Desert), where he negotiated a treaty of passage with the Ojibwe Chief Ca-sha-o-sha to continue the survey. The party then mapped its way to Lac Vieux Desert, where they learned that the Montreal River did not arise from that body of water either, but lay an additional eight days' overland pack journey away. In his report on the 1840 expedition, Cram explained "the survey could not have been carried any further, on account of having reached a point beyond which the [legal] description of the boundary ceases to be in accordance with the physical character of the country."

Cram was instructed to return the following year and complete the reconnaissance to Lake Superior. Instead of mapping the nonexistent continuous water boundary, Cram was charged with drawing two straight line boundaries connecting the center of Lac Vieux Desert to the headwaters of the Montreal to the west and the headwaters of the Menominee to the east. His crew, this time joined by Michigan Boundary Commissioner Douglass Houghton, traveled northwest from Lac Vieux Desert in search of the Montreal. After some difficulty, the party located the river, which in his report on the 1841 expedition, Cram called "but a secondary stream to say the best." Following Congress' instructions, Cram identified the river's east branch as its "main channel" and fixed its headwaters at junction of "two inconsiderable streams not more than 20 to 30 feet wide called Balsam and Pine Rivers." This point marked the western end of the straight line border measured from the center of Lac Vieux Desert.

Cram, who had identified Lac Vieux Desert as the source of the Wisconsin River the previous summer, also used this second expedition to improve basic geographical knowledge of the region. He was particularly interested in the upper tributaries of the Chippewa and Wisconsin Rivers that lay just south of the border route. Cram explored the country "laterally to the main line" and established what he called "Astronomical Station No. 3" about 12 miles south of the Michigan border on the shores of Trout Lake, where this blaze was found. This spot, which had a clear view of the heavens, was used to sight astronomical bodies with a sextant, the only reliable way of determining latitude.

Besides the first reasonably accurate description of the border route, Cram's report on his second expedition made numerous recommendations for improving the ambiguous wording of Congress' legal boundary description. Congress ignored these suggestions for five years, until Wisconsin's impending statehood forced the issue. In April 1847, the Government Land Office finally hired William A. Burt to officially survey the border. Because Congress had failed to address any of the ambiguities Cram had identified - such as how exactly to define "headwater," "main channel" or "most usual ship channel" - Burt's official border survey essentially ratified the Cram-Houghton survey, including its designation of the junction of the Pine and Balsam Rivers as the border terminus on the Montreal River. The Burt survey quietly became the legal border when Wisconsin became a state in 1848.

Forty years later, a mining boom gripped the Upper Peninsula, driven by discovery of high grade iron ore in the Gogebic Range straddling the Wisconsin-Michigan border. Built on the output of the Germania and other iron mines, the Wisconsin towns of Hurley and Montreal became thriving communities, and by 1899, the city of Ashland had grown into the second largest iron shipping port on the Great Lakes.

Perhaps motivated by this newfound mineral wealth tantalizingly out of reach, some Michiganders began to question the 1848 border. The movement to redefine it gained momentum until 1908, when Michigan re-wrote its constitution, unilaterally pushing almost its entire border with Wisconsin southward. The new border claimed almost 500 square miles of territory — along with its iron mines, farmland, summer resorts, water power sites, fishing banks, and property tax revenues – that had belonged to Wisconsin for the previous 60 years.

Michigan's argument rested on the very ambiguities in the border description that Thomas Cram had warned Congress about in 1842. In the Gogebic region, for example, Michigan claimed that the Montreal River's true "headwaters" were found on its western, not eastern branch. If so, the border terminus on the Montreal River would move substantially west and south, and the entire city of Hurley and most of Wisconsin's iron mines would be in Michigan.

Wisconsin understandably declined to participate in a Border Commission to resolve the dispute, so the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1923. After hearing mountains of evidence, none of which clarified Congress' true intent in the 1840s, the court decided in 1926 that the disputed lands would remain in Wisconsin by the weight of "long possession and acquiescence." Despite controversy and legal wrangling, the border thoughtfully hacked out of the wilderness by Thomas Cram and Douglass Houghton in 1841 remains essentially intact today.

Learn More

Have Questions?

For more information or to purchase an image of one of the objects featured in Curators' Favorites, contact our staff by email below:

[Sources: Captain Cram's reports were printed in: "Message from the President of the United States, in compliance with a resolution from the Senate in relation to the survey to ascertain and designate the boundary-line between the state of Michigan and the territory of Wiskonsin". Senate Document no. 151, 26th Congress, 2d session. [Washington, D.C.] : Blair & Rives, Printers, [1841]; United States. Army. Corps of Topographical Engineers. "Report of the Secretary of War: communicating, in compliance with a resolution of the Senate, a copy of the report of the survey of the boundary between the state of Michigan and the territory of Wisconsin". Senate Document no. 170, 27th Congress, 2d session. [Washington, D.C.] : Thomas Allen, Printers, [1842]; Martin, Lawrence. "The Michigan-Wisconsin Boundary Case in the Supreme Court of the United States, 1923-26" in "Annals of the Association of American Geographers", v. 20, no. 3 (Sept., 1930), p. 106-163.]

DBD

Posted on June 05, 2008